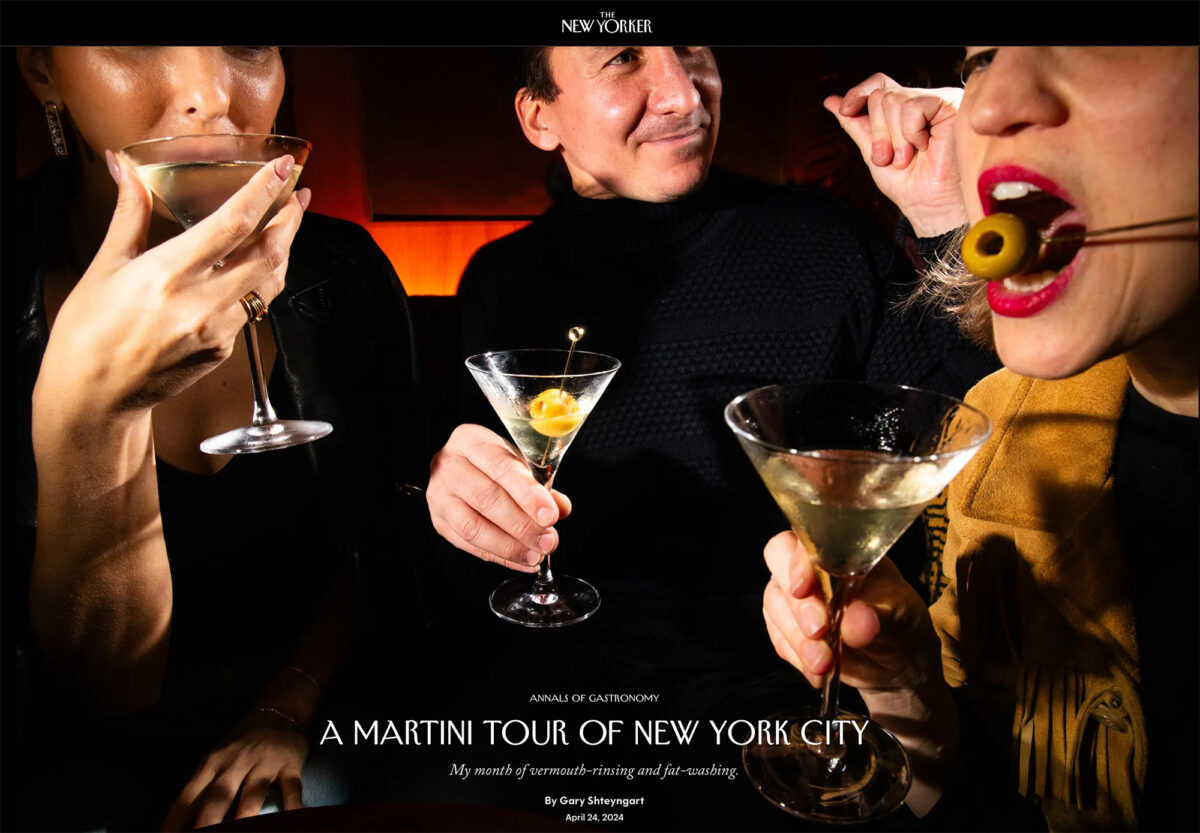

A Martini Tour of New York City

Three years ago, as the pandemic was loosening its grip on the world, and as I started to recover from the aftereffects of a botched childhood circumcision that had returned to haunt me in middle age, I rediscovered the bottomless pleasure of a cold dry Martini. My emergence from both a global and personal health crisis plunged me into a daily Saturnalia. As restaurants reopened, I unhinged my jaw and left it open: suadero tacos dripping with lard; twisted knobs of dough crowning gigantic Georgian khinkali dumplings; the mutton chop at Keens Steakhouse that is made for sharing in theory, but not in practice—all fell victim to my appetites. And to help the food go down easy, I also consumed gallons of Willamette Valley pinot noir and hyper-local artisanal ales. Soon enough, my A1C levels were in the prediabetic range and I knew that action had to be taken.

Sugar was the problem, and while I have always been an aficionado of the blood-sugar-lowering wonder drug metformin I decided to make a life-style change as well. I decided to start drinking lots of Martinis. Martinis, I reasoned, contain far less sugar than beer or wine. Also, Martinis make you happier faster and so you do not need to drink as many of them. There is a point in my writing day when a Martini appears before my eyes and I have to resist putting it in the hands of my characters. In my last published novel, many Gibsons, a relative of the Martini, were enjoyed by nearly all my protagonists as they faced lifetimes of regrets and bouts of late-fortysomething ennui. Martinis often appear in other forms of art as symbols of joy and closure. The last scene of “Poor Things,” a stylized and sybaritic film if ever there was one, ends with the sumptuously dressed characters drinking a bevy of Martinis.

But not all has been well in Martini land. For years, doctors have been telling us that a glass or two of wine at dinner is good for our health. So how bad could two relatively sugar-free Martinis be? Recently, however, doctors changed their minds. A flurry of articles descended from Mount Hippocrates declaring that the healthiest choice was zero alcohol.

Annals of Gastronomy, A Martini Tour of New York City

(Originally published in The New Yorker)

By Gary Shteyngart, April 24, 2024

Zero alcohol! A glass of water with our salad. A splash of cucumber juice after our workout. The more articles I read, the angrier I became. Modern Americans are supposed to submit to all the indignities of late capitalism: the endless work hours, the 9 p.m. e-mails from our superiors, software that monitors our every keystroke. And then we’re not even supposed to have a drink in the middle of this psychic carnage? (Perhaps that drink would interfere with our productivity.) I understand that most doctors want us only to stay healthy, but the Rx on their prescription pads seems to read “Endless suffering endured daily; refill until death.” No, I, for one, would not submit. Let the younger folks medicate with their Adderall to stay up and their benzos to come down. In the meantime, I would reach for my gin and my vermouth and one V-shaped glass to contain them all. I would dedicate myself to the cult of the Martini.

But which Martini? I divide my time between upstate New York and New York City, and both have bars and restaurants that make formidable versions of the drink. Perhaps the best Martini one can enjoy is on the porch of my home in the country, but not all readers will find themselves there. Instead, with the so-called end user in mind, I decided to find some of the best Martinis in the city and to do so with some of my favorite Martini devotees: writers, actors, critics, and other assorted dipsos.

My Martini journey began on a chilly February with my friend the writer Amor Towles. I had asked Amor, with whom I share a neighborhood and a penchant for high-quality drinking, for his favorite Martini in the city and he had mentioned the Chelsea, which was once a semi-seedy artist’s paradise and now is not. The Martini of the Lobby Bar there is beloved because it pays homage to the Dukes Martini—named for the eponymous bar and hotel in London’s St. James’s neighborhood—which is famed for its frostiness, its purity, and, not least importantly, its size. (Legend has it that patrons at the original establishment were only allowed two per evening.)

The Lobby Bar is sumptuous, with a bar top that accommodates a Parthenon’s worth of marble, and banquettes that are cozy and velvety. Amor came properly dressed in a vest for the occasion, while I had hastened off the Amtrak in my country garb. The Dukes Martini was assembled tableside—the ingredients presented on a foldout stand—by a young server skilled in the pouring arts. When it comes to the purist’s dry Martini, there are two things to remember. First, there is a mantra that Amor himself has coined: “Crisp, clear, and cold.” The Lobby Bar follows these directives by freezing the glasses, as well as the gin or vodka. The second is the “vermouth rinse.” In this maneuver, the composition I usually turn to for a dry Martini—one part vermouth to five parts gin—is almost entirely done away with. The vermouth is conscripted only to coat a rather enormous glass and is then tossed away before the gin or vodka, which has been primed with a dash of salt-water solution, is poured. (I have been told that at the original Dukes the vermouth was ignominiously tossed onto the carpet, whereas at the Chelsea it is merely splashed into a tiny glass of olives, perhaps later to be lapped up by an alcoholic dog.) Notably, no ice or shakers are used and the alcohol is neither shaken nor stirred, creating a ninety-five-per-cent undiluted Martini, which, at this volume, functions as a kind of uncontrolled insanity.

The drinking began. The first Martini, essentially a vermouth-coated container for what I eyeballed to be two and a half to three shots of juniper-noted, grapefruit-evoking Tanqueray No. Ten gin, immediately put us in a mood. The mood was a good one. I cannot remember whether it was Amor or I who said “I’m feeling very chummy.” Perhaps we both said it. The Dukes Martini came with an array of garnishes, of which I found the lemon peel most conducive to the juniper crispness of the Tanqueray.

By this point, there was no other choice but to try the Dukes Martini with Ketel One vodka. Purists insist on gin, of course, but given my national background growing up in a famous autocracy high up by the Gulf of Finland, my constitution prefers vodka for the recovery process the morning after. Nevertheless, this was a hell of a lot of vodka. Here, I plopped an olive into the oversized glass for a hint of brininess. Although my thumbs were ceasing to work, I managed to type “This is friendship juice” into my phone as Amor and I chattered away on topics both alcoholic and literary. We ordered a very decent shrimp cocktail and split a B.L.T. sandwich to fortify ourselves for our third drink, the so-called 1884 Martini. This beast is premade with two types of gin—Boatyard Double Gin, from Northern Ireland, and the New York Distilling Company’s Perry’s Tot Navy Strength Gin—which clocks in at a ridiculous 114 proof. This dangerous concoction is then fat-washed with Spanish Arbequina olive oil, after which it is frozen and the olive oil’s fat removed, while vermouth, lemon liqueur, a house-made vetiver tincture, and a few dashes of lemon-pepper bitters are added. A lemon peel is then showily expressed over the glass tableside and a very briny Gordal olive and a cocktail-onion skewer are plopped in. Although more sizable quantities of vermouth and other pollutants are at play than in the classic Dukes Martini, the over-proofed gin does a lot of the talking and one is soon very convincingly drunk.

Three Martinis in, spirits high, voices loud, we stormed down Broadway to our native Gramercy, where, in the pursuit of further bar eating and to descend from our Martini highs, we split a duo of frankfurters at the Old Town Bar & Restaurant, along with a pair of Negronis. That night, my stomach padded with beef and bun, I descended into the sleep of the righteous, dreaming of further drunken friendship still.

My research continued. I conscripted my friend the actor J. Smith-Cameron, known lately for her role as Gerri on “Succession,” into taking me to one of her favorite Martini joints, Gotham Restaurant, in the Village. One can love a bar for the drinks, or one can love a bar for the bartender. For J., it is the latter, and the Gotham bartender’s name is Billy. Gotham, which opened in 1984, has been a fixture of the downtown dining scene for decades, and Billy is a lifer in that world, having worked at Bobby Flay’s Mesa Grill for twenty years, before spending ten years at Gotham. (The restaurant closed during covid and reëmerged under new ownership.) J. and I are besotted by the man, by the excellent floral skinny tie, by the black vest, by the rolled-up bartender’s sleeves. There is a bookshelf to the left of the bar and the corporatized but still-interesting urban ballet of Twelfth Street beyond the restaurant’s tall windows, and then there is the potent drink before us.

When it comes to Martinis, Billy is a rebel against the general anti-vermouth vibe that pervades our city, but he knows his patrons prefer their libations dry. “ ’Cause most people,” he told us, “if you put vermouth in nowadays, they send it back.” He mixed us a Vesper, a drink that de-Balkanizes the conflict between vodka and gin by combining both, with a splash of Lillet Blanc serving as the Holy Spirit. “I use more Lillet to make it sweeter, to add more body,” Billy told us. The drink, while still crisp, was more toothsome than a standard dry Martini.

As we tried on a pair of Gibsons for size (here, a cocktail onion serves as the garnish), J. and I discussed child rearing. When her daughter was a child, J. taught her the rudiments of life: making a good pot of coffee and a good Martini. In a year or two, my ten-year-old son should be taught the same. J. tells me that while on the set of “Succession” she insisted that her character, Gerri, should be drinking gin Martinis with an olive, even while the other characters were drinking trendy “blue drinks” during scenes that called for alcohol. She also once threw a drink at her fellow cast member and friend Kieran Culkin because “Oh, we were very, very rude.”

Billy next presented us with a tribute to the supposed origin of the Martini, the Martinez, developed in the eponymous town northeast of San Francisco during the mid-nineteenth century. The cocktails are related, but after the crisp minimalism of a Gibson, the Martinez is akin to encountering a violent early hominid in a downtown bar. Sweet vermouth and maraschino are conscripted alongside the usual gin. Billy uses Carpano sweet vermouth, which, to my palate, provides hints of bitterness instead of overwhelming sweetness. It went down as easy as a Martinez can, and J. and I were now thoroughly drunk. Gotham’s kitchen was closed, so we headed across the street to get burgers at the Strip House to buffer our stomachs. When we left, an hour later, Billy had also crossed the street to get a drink at the bar. There he was, with his sleeves still rolled up, saying goodbye to the evening.

Over the years, I have had many Vespers with the food critic Adam Platt, and he remains, in my mind, as close as it comes to a philosopher-gourmand. “E. B. White called the Martini the elixir of quietude,” Platty, as he’s known, told me while we were sipping a vodka Martini at Tigre, on Rivington Street, on the Lower East Side. Platty’s father was a high-ranking diplomat in Asia and elsewhere when the future food critic was still a child, and he would come home and make himself a Martini. “My dad didn’t talk a lot when he had a Martini,” Platty said. But when he drank after a long day’s work, “there was a sense of slow-seeping well being.”

The dry Martini may be a powerful “friendship juice,” but a V-shaped glass is also a perfect container above which to hang one’s solitary perplexed punim at the end of a tough week or day or hour. Platty put it slightly differently: “A good Wasp just likes a big-ass Martini.”

Tigre is one of the most beautiful bars of recent vintage that I have seen. Windowless, it glows like a jewel box, and the striking semicircle of the bar is not unlike that of the U.N. Security Council, though studded with booze. Platty remarked that “all these bartenders look like Jesus,” and our handsome open-shirted server so resembled the Lord that I couldn’t help but hum, “Oh, come, let us adore him,” under my breath. The highlight of Tigre’s Martini menu is the vodka-based Cigarette, which Platty immediately qualified as “smoky as fuck.” “It’s old-fashioned, like if you smoked a cigarette while having a Martini,” Jesus told us, which is absolutely on point. Austria’s Truman vodka is shot into flaming orbit by an inventive liquor made by Empirical, the Danish distillery, and named after Stephen King’s pyrokinetic character Charlene McGee, which presents on the tongue as a flavorful burst of smoked juniper, hence the feeling that a draw of nicotine and tar can’t be far.

Platty approved. While he used to drink solely gin Martinis “colder than Margaret Thatcher’s heart,” he cited, as an inspiration for his own switch, the late Roger Angell, a writer for this magazine, who shifted during his later years “from gin to vodka, which was less argumentative.” Platty’s A1C levels, however, have also driven him in search of other pleasures. “As an older diabetic boomer,” he said, “I like to get high.”

Despite our age and lack of hair, we decided to try our luck in Brooklyn. We headed to Maison Premiere, on Bedford Avenue, which is, oddly enough, owned by the same folks as Tigre. But in contrast to our cordial reception at Tigre, we were kept waiting for almost an hour, promised a Martini, then a seat, while all around us young professionals posed with and then demolished skyscrapers of plateau de fruits de mer. “It’s age discrimination!” Platty hollered, literally shaking his fist above the din. “Where’s my fucking Martini?”

We stomped out of the Maison and angrily scarfed down some street-side tacos as we recovered from this macro aggression. We decided that while Brooklyn was, pace Cormac McCarthy, No Country for Old Men, we would give the borough one more try at Sunken Harbor Club, the recent but already renowned tiki bar above the steak house Gage & Tollner, on a dejected stretch of downtown. Sunken Harbor’s nautical theme and far more low-key clientele quickly warmed our bitter hearts as we were presented with the Immortal Martini. Here I will keep my descriptive powder dry and instead quote from the menu: “This gin Martini intrigues the senses with sesame oil, red pepper, and a cooling hint of cucumber. Not as briny as the sea, but enough to evoke the ocean’s mist.” Precisely. “It’s not bad,” Platty said. “It’s quite smooth,” he added. “I mean, it’s some weird shit. It tastes like a cucumber salad.”

We slurped in contemplation, enjoying the strangest take on the “elixir of quietude” yet, when an urgent message came over the intercom: “We’re taking on water! We’re all going down! This is your last call for alcohol!” Mist rolled into the bar, and a kind of laser-light show erupted all around us to the tune of abba’s “S.O.S.” Satisfied that we had seen the best Brooklyn has to offer, Platty and I departed for our home island.

But a few days later I was back in Brooklyn to visit my friend Matt Hranek, author of the brilliantly concise and altogether helpful volume “The Martini: Perfection In a Glass.” (Fans of Negronis might want to take a look at the accompanying volume, “The Negroni: A Love Affair with a Classic Cocktail.”)

The dapper herringbone-jacket-attired Matt—he is also the editor of WM Brown, a life-style magazine—prepared me a few Martinis using coupe glasses and cap gin, from the Côte d’Azur (“Far more herbaceous than that kind of classic London dry”). Matt is an evangelist for the “vermouth rinse” and the chilled-gin-and-glasses technique (he pointed out “the mouth feel of gin just out of the freezer” and allowed that gin-freezer storage was a “Dukes bar hack”). I want to draw attention to the joys of drinking from a coupe rather than a large V-shaped glass. A server at the venerable Death & Co., in the East Village (which makes a very effective ume-and-yuzu-aided Martini called the Parasol Dance), told me that drinking from a V-shaped glass “calls for an elegance of motion,” an elegance my shaky hands no longer have. Matt’s collection of diminutive coupes creates a different, more measured approach to the intake of vermouth-rinsed, premier-quality gin, and one with zero spillage of the precious liquid.

We crossed back into Manhattan and a six-hour marathon of Martini drinking began, one that should only be attempted by professionals like ourselves. The first stop was the new outpost of the storied Dante, this one on Hudson Street, in the West Village, which specializes in Martinis. On a Friday night, the room tinkled with the sound of voices just a decade out of summer camp and maybe five years out of the Midwest. “New York is so expensive,” a young woman from Ohio seated at the table next to us bemoaned. “But we want to pay for it!” The eponymous Dante Martini may well be worth the price: it is a heady combination of Ketel One, Fords Gin, Noilly Prat vermouth (Matt’s favorite), grappa-esque Nardini Acqua di Cedro liqueur, and lemon and olive bitters. “This is not for the home bartender,” Matt said, as he toasted with the complicated drink. “This is why you go out.” We both took a long sip. “That’s wet,” he said with appreciation.

I was most interested in the garnish, a tri-color of black, green, and red olives, and was told by the proprietor, Linden Barton Pride (a name as suitable for the protagonist of a novel as for a Martini-bar owner), that these were Cerignola olives, from the Puglia region of Italy. Matt and I followed up our drinks with some shishito peppers and one of the best Martini accompaniments I have had so far, a simple fluffy piece of bread with a side of smoked butter. The bread, Pride told me, is made in a charcoal oven and is a cross between sourdough and Turkish pide. Dante also churns and smokes its own butter. This elemental combination of butter, bread, and colorful olives allowed me to enjoy at least three more Martinis before we shoved off across town.

Our next stop would be a nostalgic one for many New Yorkers, the newly reopened Temple Bar, on Lafayette. While Dante was ablaze with light, the Temple Bar, true to its name, was dark and muted, verging on the sacred. In the old days, I recalled, this is where many affairs were kindled or allowed to slowly burn out. Matt, who has long worked in media, remembered it as a gathering spot. “A lot of finance journalists used to come here,” Matt told me, “I would walk in here and I would see the editors I knew from Vanity Fair, GQ.” He reminisced about a hostess with “Groucho Marx eyebrows” and said that the room was the setting of many of his dates. “It is what I imagined travelling on a yacht would be.”

The Temple Bar closed in 2017, after the death of its owner, and reopened in 2021 under the cocktail stewardship of the team behind the Lower East Side bar Attaboy. The décor is much the same sultry darkened Deco; even the payphone by the entrance remains. Matt insisted that we needed a protein layer to accompany our latest foray, and we chose devils on horseback to go with the “Two Plymouth Martinis very dry up with a twist,” which would serve as a foil to Dante’s eponymous drink. “Plymouth is a much sharper gin than most,” Matt mused as we sipped. The bacon of the devils on horseback set off a long Proustian moment as we recalled the Martini-accompanying bar snacks of yore, the pigs in a blanket, for example, that went so well with the Polo Bar’s Gibsons.

Duty called for us to travel above Fourteenth Street as we visited perhaps the most classic of the city’s Martini destinations, Bemelmans Bar, at the Carlyle Hotel. I would be remiss here if I didn’t mention that by this point my recollections are as blurry as the pictures I tried to take with my phone. With at least six Martinis inside me and searching for a bathroom, I spent a great deal of time wandering in and out of the Bemelmans’s brilliantly glowing maze of rooms, bumping into tourists and trying to engage in conversation the murals of Ludwig Bemelmans’s Madeline and the portrait of Bobby Short, as if they were alive and imbibing alongside me. “Tanqueray Ten,” Matt said to the server when I rejoined him. “One olive, super dry.” Although it was uncalled for, it was still sublime.

Our marathon ended at Aretsky’s Patroon, a restaurant run by the amiable father-and-son team of Ken and Gene Aretsky, who greeted us like heroes returning from a long battle, a battle we had both won and lost. Ken was the manager of the “21” Club during the booze-soaked mid-eighties, and the clubby Patroon is known for its Martinis, its enormous steaks, and the incredible photographs on the walls, including one of Andreas Feininger’s moody shots of lower Manhattan that may be the most Martini-friendly work of art imaginable.

As midnight approached, Matt and I buttressed our stomachs with a côte de boeuf for two, perfectly charred on the outside, and our last (and possibly tenth) Martini, composed mostly of perfectly dry London gin. Matt thought we should end the evening “with a bit of hydration,” and I was picturing some sort of exotic Catalan water to give the côte de boeuf a nice mineral bath, but what he actually meant was a gin-and-tonic. A cab ride home followed, about which I remember nothing.

My final Martini marathon took place at one of the few places in midtown that can make me very happy, Le Rock, the Rockefeller Center restaurant whose bar radiates warmth and civilization to a neighborhood known for neither. I was joined by the journalist and Russia specialist Michael Weiss. There have been many Wasp protagonists in this story thus far, but Jews drink Martinis as well. I once consoled a Jewish friend over the loss of his mother with help from the Smoked Martini (the Laphroaig rinse helps cut through grief) at Russ & Daughters Café, on the Lower East Side.

Perhaps my favorite bartender in the city, Connor Piazza, mixes at Le Rock. Despite her relative youth, she knows her booze and is a whiz with the cocktail shaker. Michael and I were presented with every Martini on the menu. The Au Poivre introduces vodka to the excitement of green peppercorn, and the Super Sec fixes most mortal problems with over-proofed gin and extra-dry and white vermouth. The L’Alaska is perhaps the most interesting, almost a take on the Martinez, with a sweet-but-not-too-sweet combination of dry gin, yellow Chartreuse, and a dash of the Carthusian monks’ Élixir Végétal de la Grande Chartreuse. “Without Martinis, Anglo culture would have never happened,” Michael concluded at the end of this taste-testing as I munched on soft sweetbreads with black truffle and an excellent leeks vinaigrette whose enclosure of leek greens was circumcised tableside so that the roasted white parts within could be exposed by one of the servers. “Four Martinis in an hour,” he added. “I’m bombed.”

As Connor made an In and Out, her version of a “not quite straight up, extra dry, but not dry” Martini, I recalled the first Martini I ever had. I was a sophomore at Oberlin College and my roommate’s father had taken us out to a restaurant called Presti’s, which served hard booze in a partially dry county and was popular with the faculty for that reason alone. The gin Martini tasted strange to my vodka-conditioned tongue, but the olives were nearly winking at me, and after a few of the libations my teen-aged self felt slightly less scared of the world in front of him. I remember staggering to the bathroom and endeavoring to chat up a professor of modernist American literature. I remember seeing myself in the bathroom mirror and wondering if I could somehow prove myself to be at least a little bit suave. I remember lifting up my V-shaped glass back at the table and knowing that it would accompany me through the rest of my life.

_________________________________

Annals of Gastronomy, A Martini Tour of New York City

Originally published in The New Yorker, April 24, 2024

Aurthor, Gary Shteyngart